Sunday, 20 September 2009

Links I've enjoyed this last week...

- madness at work (in a good way) , which is only set to increase due to the upcoming launch (yay!!) of Sciblogs. We've gotten some good coverage for it over the last few weeks, starting with Ken Perrott of Open Parachute breaking the news, and since then Media7 and Mediawatch have been giving us some good airplay too :)

- Today, I spent 4 hours rationalising my Gmail contacts because, well, I had synced my iPhone to them, which promptly uploaded 1000+ contacts onto my phone, many of which were ancient (i.e. any email address I've ever used in the last 6+ years), or duplicates, etc. So the only way ever to use my phone's contacts feature, was to sort it.

I am, happily, now done.

So yes, the links (bear in mind that many of them end up making their way into our weekly newsletter as well, and so don't appear here)...

Sneak test shows positive-paper bias

Published in Nature, this confirms what, yes, we already know. But still interesting, and good to see it testably confirmed. And I can understand where the bias comes from although it's hardly something I'm in favour of (particularly as the originator of some genuinely negative results myself).

The Secrets Inside Your Dog's Head

An awesome article by Carl Zimmer about dog behaviour and evolution and research and things. As the owner of a dog myself, I found it particulaly interesting, but I imagine that anyone who's encountered our four-legged friends might find it interesting.

The Briefly Series

Ep. 1: The Big Bang. An awesome science communication idea, the point is to take major concepts in science and explain them not only clearly and briefly, but really well visually as well. Kudos to all the people who given freely (literally) of their time to do this.

Futurity

A completely different type of outreach, Futurity takes the research releases of a number (some 35) top American universities and publishes them in one awesome website. It's great reading, but I have two small concerns: it is, in essence, a collection of press releases (not a bad thing, just something to be aware of when reading the articles) and it does not necessarily give an accurate idea of when the research was published etc. I've notcied a couple of things on the site that seem to be really new/recent, but which I know came out some weeks ago. Nonetheless, good site.

Interphone and the US

Or not, as it turns out. I don't know how I missed this, but it would seem that the US has not taken part in the Interphone survey. * significant pause * I know. Which means they're now considering, I dunno, replicating the work? Or something? It's a big pity, firstly because the data from the US would no doubt have been really good (a very large market who were early adopters of the tech), and it also seems a waste of money to even consider doing it in an American context. Of course, one also has to ask: if Interphone's results are good enough for everyone else, why wouldn't they be good enough for the States?

Tuesday, 15 September 2009

Shrodinger's tobacco mosaic virus

Thursday, 10 September 2009

Nature's data-sharing issue

There's a lot of interesting stuff in here, including articles about what seems to be a growing (or at least increasingly loud) movement to open up the acecssibility of data, particularly in the Life Sciences. There's even been talk of scientists sharing prepublication data to try speed things along a little...

Of course, there's also analysis of what happened to the ideal of data sharing , and the problems range from difficulties with the technology of it, particularly in areas where good, strong databases (and sharing habits) are not common, to problems with formats, preconceptions, and, frankly, habits.

Tuesday, 8 September 2009

Peer Review Survey 2009 - the system's worth keeping, but could use some work

Rather than simply reprinting the results (which can be downloaded by clicking on the hyperlink in this page), I thought I'd also have a look at the results themselves, and see what comment, if any, I could furnish.

Right, then.

The questionnaire, which was conducted for 2 weeks, was sent out to some 40,000 researchers, all of whom were published authors. Of this 40,000, 4,037 (10%) completed the survey. Of that 10%, 89% classed themselves as 'reviewers'.

Of course, my first question at this point is whether this is representative of researchers as a whole...Do 89% of all (published) researchers review? Or was there some intrinisc bias towards the subject that meant that people who review were more likely to complete the questionnaire (and hence skew the findings...)

Moving on.

Satisfaction

In general, respondents (not reviewers) were fairly happy with peer review as a system - 61% were satisfied (although only 8% were very satisfied) with the process, and only 9% were dissatisfied. I would dearly loved to have been able to organise a discussion or two around that latter 9% or so, to figure out why (which is qualitative research is so important).

Reviewers generally felt that, although they enjoyed reviewing and would continue to do it, that there was a lack of guidance on how to review papers, and that some formal training would improve the quality of reviews. There was also the strong feeling that technology had made it easier to review than 5 years ago.

Improvement

Of those who agreed that the review process had improved their last paper (83% of respondents), 91% felt that the biggest area of improvement had been in the discussion, while only half felt that their paper's statistics had benefited. Of course, and as the survey rightly points out, this may because this includes those whose papers contained no such fiddlies...

Why review?

Happily, most reviewers (as opposed to respondents, which includes reviewers and the leftover authors) reviewed because they enjoyed playing theire part in the scientific community (90%) and because they enjoyed being able to improve a paper (85%). Very few (16%) did it as a result of hoping to increase future chances of their paper being accepted.

[On that point - is that last thought/stratagem valid? Does reviewing improve one's chances of paper acceptance in any way?]

Amongst reviewers, just over half (51%) felt that payment in kind by the journal would make them more likely to review for a journal - 41% wanted actual money. (then again, 43% didn't care). 40% also thought that acknowledgment by the journal would be nice, which is odd considering that the majority of reviewers favour the double blind system (see below), or even more strangely, the fact that 58% thought their report being published with the paper would disincentivise them, and 45% felt the same way about their names being published with the paper, as a reviewer. [Note:in the latter point, for example, that 45% does not mean that 55% would be incentivised - a large proportion of the remaining 55% is in fact taken up by ambivalence towards the matter]

Amongst those who wanted payment, the vast majority wanted it either from the funding body (65%) or from the publisher (94%). In a lovely case of either solidarity or self-interest, very few (16%) thought that the author should pay the fee. Looking at that 94% of authors who would want to be paid by the journals to review - where would this leave the open access movement? One of the major, and possibly most valid, criticisms currently being leveled against paid subscription journals is that their reviewing is done free of charge. Indeed, it might even lead to a rise in subscription prices, meaning even more researchers are unable to access paid content. Hmmmm.

To review, or not to review

The most-cited reasons for not reviewing were that the paper was outside their area of expertise (58%) or that they were too busy with their own work (30%). Of course, the first point does suggest that journals could, and should, do a better job of identifying which papers should go to whom...Certainly, this would be a brilliant place for a peer-review agency to start!

The mean number of invitation to review rejections over the last year was 2, but a little a third of respondents would be happy to review 3-5 a year, and a further third 6-10! Which suggests a great deal of underutilisation of the resources, especially considering that the primary reason for not accepting an invitation to review is that the reviewer and subject weren't properly matched.

Purpose

For this, I'd suggest the best thing to do is have a look at the graph below (which is from the report, again to be found here).

(c) Sense about Science, Peer Review Survey 2009: Preliminary Findings, September 2009, UK. Click on image to enlarge and make more legible.

(c) Sense about Science, Peer Review Survey 2009: Preliminary Findings, September 2009, UK. Click on image to enlarge and make more legible.What is interesting is that peer review is underperforming significantly on some of the functions felt to be most important, namely the identification of the best manuscripts for the journal and originality (assuming that by this they mean something along the lines of 'completely novel and ground breaking', then there's a very interesting discussion to be had around that, considering that PLoS specifically doesn't look to that, something I talk about in this post).

It's also performing poorly at the detection of plagiarism and fraud detection, although one wonders whether that is a realistic expectation (and, certainly, something that technology could perhaps be better harnessed to do).

Types of review

Most (76%) of reviewers felt that the double-blind system currently used is the most effective system - usage stats were thought effective by the fewest reviewers (15%).

Length of process

Gosh. This was interesting. So, despite the fact that some 75% or reviewers had spent no more than 10 hours on their last review, and 86% had returned it within a month of acceptance of invitation, 44% got first decision on the last paper they had submitted within the last 1-2 months, and a further 35% waited between 2 and 6+ months.

Of course, the waiting time for final acceptance scales up appropriately, as revision stages took 71% of respondents between 2 weeks and 2 months. So final acceptance for took 3-6 months for a third of respondents, and for a further third, could take anything between that and 6+ months.

Now, I can understand that the process is lengthy, but it does seem like there's a fair amount of slack built into the system, and it must have something of an impact on the pace of science, particularly in fast-moving fields. I don't have an answer, but Nature is just about to release some interesting papers discussing whether scientists should release their data before publication, in order to try prevent blockages...(UPDATE: Nature's special issue can be found here).

It's worth mentioning, despite whatever I may say, that slightly more respondents thought peer review lengths were acceptable (or better) than not. Comment, anyone?

Collaboration

The vast majority of reviewers (89%) had done the review by themselves, without the involvement of junior member of their research group, etc. While I can understand this, to some extent, I wonder whether it doesn't inform the feeling that some sort of training would be useful. Could a lot of that not be provided by involving younger scientists in the process?

Final details

Just over half (55%) of respondents have published more than 21 articles in their career, with 11% having published over 100. Not much comment there from me, other than O_o!!

89% of respondents had reviewed at least one article in the last year (already commented on this, above).

For those interested, most respondents were male,over 36 years old, and worked at universities or colleges.

While half worked in Europe or the US, 26% worked in Asia (to be honest, I was pleasantly surprised that the skew towards the western world wasn't larger), and the most well-represented fields were the biological sciences and medicine/health.

So yes! there you have it - a writeup that's a little longer than the exec summary, but a little shorter than the prelim findings themselves.

It does raise a number of interesting questions, particularly around the role of journals in the process, but it also confirms what I think we've all heard - that while science publishing is going through some interesting times, very few would dispute that peer review itself is anything other than very important to the process. Although it might need to do a little bit of changing if it's to remain as important as it is currently...

Monday, 7 September 2009

Reflexology quickie

In essence, it says that the evidence for reflexology working is, well, not there. Yes, the foot rub is quite cool (apart from the excruciating pain and the need to spend some time thereafter limping), but really, one could just get a normal foot rub instead.

In fact, thinking about it: perhaps normal foot rubs are actually better, as they don't force one to tense every muscle of the body in agony, something which I battle to see as being conducive to one's health and wellbeing.

Name-dropping makes you obnoxious

And yes, intuitively, I guess many of us do. Despite this, it still doesn't stop many people doing it, on a regular basis. Some might even say that networking somewhat encourages it. Well, networking as seen in a very narrow, and unlikeable, light (happy to write more on that subject, should anyone wish).

So yes, some German researchers have finally looked into the phenomenon, and found the following:

If you meet someone, and find out that they share a birthday with someone likeable, or that they know someone interesting, then you may perhaps feel sunshinier towards them, but only if they didn't tell you directly. And context is also pivotal.

If, on the other hand, you drop into conversation that you are good mates (or whatever) with someone famous, particularly if you volunteer the information fairly directly, then people are less likely to like you. So not a good strategy. Boasting does not make you friends. Hear me on this.

Actually, thinking about it, perhaps that's some of the appeal of things like Linkedin (apart from the obvious) - people can see how very cool and amazing your connections are, without you ever having to vouchsafe the fact. Now, who has some amazing contacts me to link to?

The article about the research can be found on Scientific American's website, here.

The travelling salesman problem and bacterial computers

Witticisms aside, the first thing that came to mind was the travelling salesman problem, a lovely little piece of computational maths. To give you the gist: it's all about a travelling salesman, who has to figure out how to optimise his sales route so that he only visits each place once, and completes the route in the shortest possible distance. It's been the focus (well, sort of) of such things as genetic algorithms (which can be used for all sorts of fascinating things, and I'd strongly advise that you explore the area further), and now a new field called bacterial computing.

Bacterial computing fuses mathematics and biology to compute problems - sort of like genetic algorithms on 'roids. And recently, it was used to solve something called the Hamiltonian Path Problem, which is similar to that issue faced by our anonymous, but hopefully ubiquitous, salesman. The Burnt Pancake problem also features, which name I am endlessly amused by. Also, there's an unrelated, but darkly amusing, xkcd strip about pancakes.

The whole field is called, enticingly, 'synthetic biology', and the brains behind it reckon that it has uses not only for solving fun maths puzzles, but also for more concrete uses such as medicine, energy and even the environment.

Anyway, the paper can be found here (it was published in the Journal of Biological Engineering, which, given its name, I expect to be presenting me with a means of having gills as well as lungs sometime very soon).

Sunday, 6 September 2009

Magnetic monopoles?

Only 2 days after a New Scientist article discussing some 13 phenomena that science is still unable to understand - including the fact that magnets don't seem to come in a fashionable, slinkier 'monopole' - it's been announced that, in fact, they do.

Haha.

To paraphrase, for those too busy (or uninterested, in which case stop reading), I shall make the attempt:

Magnetism and electricity are very strongly interwoven, as everyone who's done highschool physics knows. However, while we are able to see component parts of electricity - electric charges themselves, such as electrons - the same doesn't hold for magentism. Magnets always come in 'North and South' flavour.

Now, clever people who theorise about these things are sure they must exist, but we just hadn't seen any of them yet. And we can't make (apparently) them either. But we had hope.

And now, vindication! Wahay! Well, sort of. We have, in fact, observed the next best thing to them, says a paper to be published in Science (which means it's probably not a hoax). In essence, two different groups of researchers have dug up differing evidence of these analogues.

Also, the scientists got excited about things like fractioning in 3D and so forth, but this went somewhat over my head...Actually, most of it did, but nonetheless, still very cool.

Saturday, 5 September 2009

Cows and...seaweed?

In no particular order, some of the more recent ones:

The NZ Herald: Hungry bugs could slash animal-gas danger

The register: Bubbly-belly-bugging boffins battle bovine belch peril (possibly the best headline I've yet seen, and it sort of fits with the country responsible for more video tracking of its citizens than any other)

Sciencealert: Diet may cut cow fart emissions (perhaps the most direct headline)

The interesting thing is that this last strategy, if it works, could be perfect for New Zealand. We have access to lots and lots of seaweed, and lots and lots of cows. And while I'm fine with GM, I think Occam's Razor is a great guideline, and something like this is less likely to come with the usual hysterical press-release battles, and potentially unseen side-effects, possible with messing the bugs themselves (for example).

If anyone's really interested in the issue, I can happily supply more resources (and even a podcast)...

The geoengineering debate

The Royal Society of London has released the results of a year-long study into various geoengineering options, and have looked at them in terms of cost, risk, and so forth. More on the report can be found here (also, the 2020Science blog has some good posts on it as well).

Click on image to enlarge. Preliminary overall evaluation of geoengineering techniques (Royal Society of London, Geoengineering the Climate, Sept 1 2009)

Click on image to enlarge. Preliminary overall evaluation of geoengineering techniques (Royal Society of London, Geoengineering the Climate, Sept 1 2009)The reason it's sparked comment is that people are concerned that the techniques, even the safest of them, might cause downstream problems we can't predict. The report was, however, pretty clear on the fact that emissions reduction should absolutely be seen as the primary goal, and that geoengineering efforts should be a 'last ditch' strategy.

Some comment on the matter can be found here and here.

I must say, I agree with the need to further consider these options. Yes, we need to look at mitigating emissions, of course, but if Kyoto is any indication, we stand the real possibility of failing to reach the various global and country-specific targets to be set in the upcoming year or so. And it is highly likely that new technologies are yet to be invented which will help in these efforts. But a plan B is generally a good idea - even if we never implement such measures, better to plan for them now than, in 10+ years' time, to realise that such measures are necessary, but cannot be implemented in a timely fashion.

Also, there's the pure geek joy of simply contemplating huge mirrors on the sky (having said that, Futurama has already warned us of the potential pitfalls of such a technology).

Jellyfish, continued

I think I like the small blue jelly best, just because it really does look like a graphic generated for a show such as Fringe (yes, this last link really does point to Fringepedia's page on the graphics used in the show). Of course, the rest of them look like something cooked up in the fevered imagination of a sci-fi/fantasy artist at the point just before the absinthe abuse of the night causes them to pass out...

Pretty produce

So yes, a few new instances of pleasantly pretty produce. In first place (because I live in NZ, if nothing else), are some very special red apples.

A local scientist, Dr Richard Espley, has been working on understanding the genetic mechanisms behind the red colour in apples, with the idea being that apples can be grown which have novel colour characteristics, as well as oodles of anti-oxidants. And when I say red apples and novel colour characteristics, I mean it: not only will the skins be red, but the flesh of the apples as well. Apparently, apples with red flesh do exist, but while they have ligher levels of good things (liek antioxidants), they don't taste nearly as good as their white-fleshed counterparts.

Richard won awards at the recent MacDiarmid Young Scientist of the Year awards, and works at Plant and Food, one of New Zealand's Crown Research Institutes.

Next on the list, and perhaps slightly more flippantly, are heart-shaped cucumbers.

Yes, you heard me correctly: from the people invented bento box art (links abound), comes the next element in making the everyday necessity of nutrient ingestion a more pleasant affair. Other shapes include stars, and who-knows-what next.

And, hilariously, baby-shaped pears.

The Chinese farmer involved has been perfecting his technique for some 6 years by now (well, that's what I read), and they're selling for £5 a pop. I think they're very reminiscent of the Buddha, don't you?

Of course, if these had been made in the shape of other deities, I can imagine there may have been more of a fuss (although, if you've ever thought of making truly iconic toast, have a look here, and I've also seen various kits and DIY vids on google as well).

But yes - hooray for those tirelessly endeavouring to beautify our meals.

Wednesday, 2 September 2009

PhD Comics gets it right, again

Clicking thereon will show it in a slightly more readable form, for those of you not blessed with supervision.

And, of course, this one as well.

Monday, 31 August 2009

Google Transit

My happiness, however, turned to ecstatic delight when I realised that Google Transit is far, far better than the Metlink website. A thorn in my side, I find the journey planner on Metlink's website silly - it requires that one have the correct street number if it's to find a bus stop, for crying out loud, rather than simply pick up up stops in the area of the one requested. in a move of quite stunningly bad programming, it's more likely to try match street numbers than street names, leading to a great deal of gritted-teeth frustration...

Honestly, one would think the search and databasing advances of the last x years have never happened, with the required follow-up of 'y'?

Transit, however, has Google cleverness built in. How absolutely tech-tasty, and a godsend for those of us stuck with crappy transport information systems. Now, of course, all we need is to be able to check bus times - my bus, for example, is 5-15 minutes late almost every day, but, well, I can't exactly take it for granted, can I? Sod's law always applies, and I'd rather wait for 10 minutes before hand than half an hour afterwards...

Aah, I miss TFL sometimes. OK, so it didn't always get the shortest route right, but it did keep track of what was running late. Then again, I've heard that Wellington buses are beginning to have GPS trackers installed which should help the problem, although then again, possibly not - after all, it's not just the data itself, but what's done with it, that makes or breaks a system (see above paragraphs).

So yes - I'll be waiting (inevitably, given the buses here) to see what happens, but in the meantime I'm glad that I can at least find bus routes without having to try magically figure out which street number will give me a result...

The value of knowledge economies

In it, he basically lays out why a knowledge-based (or at least heavily contributed to-) economy is something New Zealand should be striving for.

And I have to say I agree: this idea that one must make things in order to be a wealthy economy is, well, extremely outdated - certainly, it seems to have landed NZ in a bit of a pickle economically. I remember being told years ago, while studying business, that manufacturing and farming-based economies would contribute an ever-decreasing amount of wealth to the economy due to, well, a number of reasons really, including the ever downward pressure on commodity prices, manual labour, and, frankly, China.

Or, think of it using the internet vs print as a paradigm: the people who generate content (goods) are increasingly squeezed, while the people who can add value to the content, like coders and tech companies (services) find themselves doing increasingly well.

So yes, a knowledge economy it is! And it's something other countries, including India and Singapore, cottoned on to some time ago.

The only thing is: how to get one (properly) going here? Of course, we need skilled people - not that they necessarily have to have degrees, mind you. But highly skilled, yes. And, and this is simply a perhaps (and one written from a non-kiwi point of view), perhaps we need more people? I know that the kiwi government makes it pretty difficult for people to come live here and while I can understand that attitude for minimally skilled people, I tihnk that they may want to consider loosening things up for young/older highly skilled people who can both contribute to the market, but also help increase the market size itself (a significant issue here).

And the industries themselves? Well, they're likely to be in tech, design and science, predominantly (and, of course, in the intersections between the aforementioned) - these industries really do foster knowledge economies, and government investment in them is very important. Let's hope the government realises that.

Personal space issues: now we know the 'where'

In a recent coup (haha), they appear to have figured out the whole 'personal bubble' issue. Well, to be more precise, they've figured out which brain structure is responsible.

Fascinatingly, it's the amygdala. This is the region in our brain responsible for feelings of fear, anger, and other strong negative emotions (I'm sure it was mentioned in the last episode of Fringe, actually).

It seems that lesions or other 'damage' or dysfunctions in the amygdala mean that the person in question is comfortable at closer proximities to others than is usually the case. In fact, it appears that, for some people at least, they have no sense of personal space at all - they can feel completely comfortable standing nose to nose! Which makes me wonder: do all the people in those chewing gum ads people have dysfunctional amygdalas?

Happily, the researchers also considered the role that culture may play in perceptions of personal space: I know from personal experience that these can vary widely, and consequently cause a fair amount of unease in the person used to a larger bubble. Apparently, they think that culture and experience may, over time, affect the brain and how it responds to situations (yes, the brain is plastic and learns...). Makes sense.

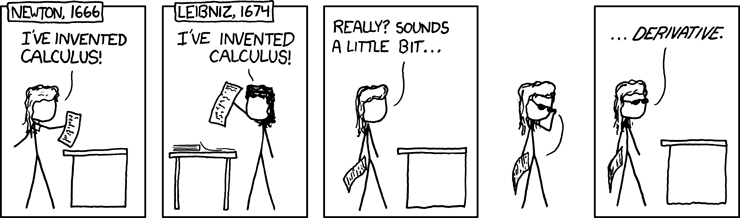

xkcd: Newton and Leibniz

Tuesday, 25 August 2009

Gadgets, Games and Geeks 09: The Future of Innovation, Shatter, Weta and pizza

And yes, it was pretty interesting.

The highlight for me was Bill Reichert's talk, 'The Future of Innovation: Entrepreneurship, Venture Capital and Emerging Technologies' (if you're interested, you can find the talk and accompanying slides on the SMC's website, here). He's a very engaging speaker, and had some great pieces of knowledge to impart.

Certainly it got me all inspired again about entrepreneurship - a subject close to my heart as it forms one of my qualifications. And, while much of it absolutely seemed like common sense, there were a couple of surprises, particularly the 'change takes time' point he makes (point 9 in his talk). Essentially, he says that we've talked ourselves into believing that the pace of change is accelerating, but that it simply is not the case. We simply need to look, he says, at how long it has actually taken us to get, for example, to high bandwidths and oodles of storage or, for that matter, electric cars which aren't completely useless (or incredibly expensive). Other examples abound (really, have a look at his slides).

I also found his point about Twitter very interesting (towards the end of the session, in response to a question from the audience). He said that his issue with Twitter was simply that it gave entrepreneurs the wrong idea: that they could come up with a clever idea, get a few million 'eyeballs', and as a result make (lots of) money off it. After all, the jury is still out as to whether Twitter itself can make money, and how.

Having said that, it was definitely encouraging to hear that it's not all doom and gloom - actually, a personal belief I've heard mirrored many times is that tough times actually enhance creativity by shocking everyone out of their bubbles. So we should have lots to look forward to.

I also found Sidhe's talk very interesting (I have recorded it, and can put it up if requested - the slides can be found here). James Everett did a great job of explaining who Sidhe are, why they want more game developers in Wellington (amusingly, 'because it's difficult to poach from yourself'), and where they're hoping to go in the future.

And I am definitely intrigued by there idea: shorten development times, shorten game lengths and bring down prices. Sounds like just my type of gaming. And Shatter really is very, very cool. Yes, it's pong, but it's new pong, and gosh is it pretty. If only it was available for PC...

Sadly, I found the talk by Tim Lauder of Weta Cave a little less thrilling than the previous two, although, as a lifelong fan of steampunk, I did enjoy the whole Dr Grodbert's thang (I almost bought a lapel pin!)

I think my only real complaint was that I think there could have more exhibitors. I have some theories on why there weren't (nothing I'll air, of course), but it really would have been a wonderful way to showcase some more work. For example, I know a guy up in Palmerston North whose company, Unlimited Realities, has been developing Dell's new touchscreen software...

On the other hand, the enormous slices of pizza which rounded (haha) the evening off were brilliant.

So yes, here's to GGG09, and hoping that GGG10 is even better!

Monday, 24 August 2009

Addendum to previous post

JOVE, or the Journal of Visualised Experiments, is a fantastic idea. Anyone working in the biological sciences will, I'm sure, appreciate how tricky it can be to learn or duplicate a new methodology, and its this problem which JOVE aims to solve.

In essence, it's a peer-reviewed, (although no longer OA, sadly) journal where the content is all video, rather than words.

Sunday, 23 August 2009

The threat challenge to science publishing

An article I recently wrote for the Science Media Centre (note, there's a really cool sound recording from the WCSJ on the SMC website, here). The debate's a complicated one - this article just manages to lightly touch upon some of the issues...

The Open Access (OA) movement has been around since the 1990s – not surprising, as one of its principal tenets is that information should be freely available online. More specifically, it generally refers to scientific information, and in particular the information generally found in scientific journals. As we all know, this information is generally not freely accessible: rather, it is usually kept for access by journal subscribers, whether they be individuals or institutions.

The debate over whether scientific research should be freely accessible or not is a heated one, with very little signs of a resolution either way anytime soon. Its proponents say that freely available scientific research advances the cause and progression of science. Its detractors says that without journals (most of which are subscription-based), there would be no peer-review process, and hence no quality control. It’s not that simple, however.

Perhaps a good place to start is with the inevitable. Michael Nielsen has written a very clear article on the matter, entitled ‘Is scientific publishing about to be disrupted?’. In it, he argues very convincingly that scientific publishing (including journals) is about to experience the same upheaval that the newspaper/print industries have been experiencing. At the hands of the same phenomenon: the internet. And, just like newspapers, there is relatively little that can be done about the situation.

One of the most important, and perhaps noticeable, agents of this change is scientific blogging: blogs written by scientists about their own and others’ work.

As Nielsen writes:

“Let’s look up close at one element of this flourishing ecosystem: the gradual rise of science blogs as a serious medium for research. It’s easy to miss the impact of blogs on research, because most science blogs focus on outreach. But more and more blogs contain high quality research content.”

They differ greatly from published articles in that they allow scientists to engage in an ongoing conversation about their work and its developments, and are also a valuable means of engaging other scientists in a conversation about their work.

The movement is catching on to such a degree that numerous highly respected scientists are blogging, including Terry Tao, Tim Gowers, and Richard Lipton (list supplied by Michael Nielsen). On home ground, the New Zealand science blogging movement is also picking up pace: there are a number of blogs already in existence, and there are plans afoot to aggregate these bloggers’ work in a project called Sciblogs (based on ScienceBlogs).

“Scientific publishers should be terrified that some of the world’s best scientists, people at or near their research peak, people whose time is at a premium, are spending hundreds of hours each year creating original research content for their blogs, content that in many cases would be difficult or impossible to publish in a conventional journal. What we’re seeing here is a spectacular expansion in the range of the blog medium. By comparison, the journals are standing still.” (Nielsen)

A main feature of the Open Access movement, however, is not necessarily to dissuade scientists from publishing journals (more on that later), or to encourage them to write blogs. Instead, it aims to encourage them to deposit copies of their published papers (pre or post-prints) in repositories which do give free access. Of these, ArXiv is particularly prominent, and has a fantastic physics blog.

A recent issue of the Australian (OA) journal SCRIPTed looks at the issue in a paper entitled “Open Access to Journal Content as a Case Study in Unlocking IP’. The paper examines the accessibility of reviewed, published papers from examples of the different types of science publishers, including PNAS, Elsevier and a major division of the US NRC.

Interestingly, the paper finds that the lack of access to published papers is not, as one might assume, solely the fault of publishers. Instead, it found that the publishers’ copyright restrictions were (relatively) liberal, in many cases allowing researchers to place their work in repositories of one form or another. The primary reason for the lack of forward momentum was due to the researchers themselves. In the paper’s conclusion:

“The exploitation of the opportunity has lagged, because of impediments to adoption, especially the lack of any positive incentive to self-deposit, and downright apathy. The outcomes to date are disappointing for proponents of OA and Unlocking IP…OA and Unlocking IP in the area of journal articles are at serious risk of being stillborn’.

No doubt, this last sentence is one which would thrill many journal publishers. However, the OA movement and blogging are not the only movements which threaten journals. These previous examples have opposed journals in a relatively passive way – they are (generally) quite happy to co-exist.

There is a far stronger movement which is lining up against journals. This movement, written about in Times Higher Education’s recent article ‘A threat to scientific communication’ talks of growing unhappiness with publishing papers as the measure of a scientist’s success. An increasing number of (well respected) scientists, including the former editor of the British Medical Journal, says the influence of being published in the ‘major’ journals is far too powerful, and that journal metrics such as the Journal Impact Factor are actually an impediment to scientific progress.

“"(Journal metrics) are the disease of our times," says Sir John Sulston, chairman of the Institute for Science, Ethics and Innovation at the University of Manchester, and Nobel prizewinner in the physiology or medicine category in 2002.

“Sulston argues that the use of journal metrics is not only a flimsy guarantee of the best work (his prize-winning discovery was never published in a top journal), but he also believes that the system puts pressure on scientists to act in ways that adversely affect science - from claiming work is more novel than it actually is to over-hyping, over-interpreting and prematurely publishing it, splitting publications to get more credits and, in extreme situations, even committing fraud.”

A further comment:

“Noting that the medical journal articles that get the most citations are studies of randomised trials from rich countries, [Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet] speculates that if The Lancet published more work from Africa, its impact factor would go down.

“"The incentive for me is to cut off completely parts of the world that have the biggest health challenges ... citations create a racist culture in journals' decision-making and embody a system that is only about us (in the developed world)."”

(Another problem cited is that the JIF, because it focuses only a few years, actually gives no indication of the long-term importance of scientific work.)

Embargoes are also coming under attack (see the recording at the bottom of this page), as it makes science seem more like an event than a linear series of incremental advances. This reminds me quite a lot of Professor Sir Peter Gluckman’s recent comments on the NZ media: what he said very closely matches this criticism, in that he feels that the New Zealand media fails to show science as a gradual process, instead showing it as a series of leaps forward. Which gave me cause to think: is it, then, actually the media’s fault? Particularly here in New Zealand, where many journalists are not able to specialise in science issues, and thus gain an understanding of scientific research’s continuity?

But I digress. In answer to the journals’ primary defense of their existence, the peer review process itself, there is also increased questioning of its use. Journal publishers maintain that the peer review process is the only real means of quality assurance for scientific research. The reactions to this include the following:

- That peer review itself is generally undertaken for free, meaning that journals are taking free work and, essentially, selling it back to scientists.

- The peer review process itself needs to have some of the following questions asked about: who actually does the reviewing? How appropriate are they? How strenuous is the process? And, of course, timing is also an issue (the process can take months, greatly slowing the speed at which research becomes known about).

- In fact, this latter point brings to mind the recent debate over a paper published recently by well-known climate change skeptics, which attributes over 70% of climate change to the El Nino/Southern Oscillation weather patterns. While the paper was peer-reviewed, there have since been rebuttals (including this, yet-to-be-published paper) saying that the maths used was incorrect, and bringing into doubt the quality of the peer review undertaken on the original paper (I’m not commenting on either, please note).

- [for more on peer review, have a look at this post, about the recent results of a survey into the matter)

Deep thought also has to be given to the tremendous amounts of research lost because it doesn’t come up with a result. There are two types of experiments which have no end results (and I speak from personal experience here): they were poorly set up, performed or analysed, or there simply are no results to be had.

While the first group should absolutely be ignored, the second can be very important to scientists. We used to say (in the market research consultancy at which I worked for a time) if our analysis turned up nothing that “it’s a learning in itself’. And it often can be, either to prevent other scientists duplicating the same research (a huge waste of time and resources), or because there really is nothing there to see, which suggests that effort be focused in another direction.

The remedy for science publishing's woes is unclear. While everyone agrees that there is a problem, or at the very least a challenge, nobody is sure what shape the future of science publishing will take.

Michael Nielsen says that scientific publishers need to become technology-driven if they are to survive (he mentions Nature as one of the few publishers trying this), and that they must do so even if it means fundamentally changing the way they currently work.

“In ten to twenty years, scientific publishers will be technology companies. By this, I don’t just mean that they’ll be heavy users of technology, or employ a large IT staff. I mean they’ll be technology-driven companies in a similar way to, say, Google or Apple. That is, their foundation will be technological innovation, and most key decision-makers will be people with deep technological expertise. Those publishers that don’t become technology driven will die off.”

And while it seems that the peer review process is likely to stay, it will no doubt change in form. It might well imitate what PLoS's policy is, which is to check that the results can be substantiated by the methods and data, but not to worry about whether it is original or even important – this should be up to the world at large to decide.

Of course, something else to consider is this: if a paper is published in a repository or on a scientist’s own website/blog, and is then commented on by his peers…Is this not exactly what the peer review process is anyway? In that case, why be concerned with publishing?

However one looks at it, the industry is in for a massive upheaval: while it is uncertain just how, we can be sure that those trying to innovate to stay ahead of it may survive, but those that stand still will, like their newspaper counterparts, face extinction.

Note: The Royal Society of New Zealand conducted some research in journal use/publication in 2004. The results are here.

Further note: the original title has been changed to include 'challenge' after some commentary about whether 'threat' was, in fact, the correct word (I admit, it probably wasn't the best)

Thursday, 20 August 2009

Global warming warning

Not, I hasten to add, because I think it's funny in and of itself. And the article itself is very calm and cogent about things. It's simply that the headline reads somewhat like an old, retro doomsday prediction.

And no, I'm not a denier. I'm not even a skeptic (although I would definitely say I'm a pragmatist). To be honest, it's not something I feel that I am nearly well-informed about to comment on.

Happily, a number of other people are doing very fine jobs of commenting on the issue: Hot Topic is a great example, and the Science Media Centre tracks what's happening in the coverage.

Tuesday, 18 August 2009

Gamma-ray bursts get even more sci-fi

They're the most impressive explosions the universe has been able to offer after the tremendous effort of the Big Bang. If one happened anywhere near Earth (and by near I mean within a thousand light years or so, so 'near' only a cosmic scale) and and was pointed at us, the radiation would kill all life here. Even the cockroaches (probably).

Up until now, prevailing thought had it that they were formed by the collapse into a black hole of a supermassive star. Now, however, a new theory is being considered (again): that they occur as the result of a black hole burrowing into the middle of a star and then consuming it. A sort of cosmic Alien, if you will.

Happily for us they're directional, and it seems that they're more likely to happen on the outer edges of the universe. Scientists have posited that this is because that's where the older stars are, and the differences in chemistry between older stars and newer stars means newer ones are more likely to be prosaic about the matter and avoid the huge effort involved in producing a gamma-ray burst. Maybe. Another theory says they occur in regions with low metallicity (not a feature of the Milky Way, happily).

Either way, they're fascinating beasts and something to keep an eye on (possibly one wearing sunglasses). For those of you interested, we apparently pick up about one a day...

More evidence that cockroaches may be the pinnacle of evolution

Alright, for those of you who prefer accuracy in your statement: no, they're not really the pinnacle of evolution, for after all the theory somewhat precludes such a notion. But they are remarkably resilient. I had a few doozies in the kitchen of an ancient house I inhabited at one point in Cape Town, and I can confidently say that they're well-nigh unstoppable, particularly if they're big and old.

Back to the point of the post, though: it's come to light (unlike the creatures themselves) that not only are they capable of withstanding nuclear fallout, but that they could also survive climate change. Apparently, they are able to hold their breath in order to conserve water loss - a particularly useful trait in Australia, where the research was conducted.

I'll happily admit I quite admire them. They're a brilliant example of how 250 million years of evolution can give one, if not backbone, then at least a pretty remarkable exoskeleton.

Monday, 17 August 2009

Sunbed silliness

And it's become a rather heated (haha) issue here in New Zealand, particularly as it's now been confirmed that sunbeds are, well, synonymous with cancer causation. The IARC is behind the research and they tend to know what they're talking about (in fact, they're the WHO's agency committed to looking into human cancer).

Some countries have legislated around this, either by banning their use altogether, or by requiring that it is confined to adult use. In other cases, they allow teenagers to use them, but only if there has been adult consent.

But in New Zealand, none of this is the case. The sunbed industry here operates under a voluntary code (generally code for 'pays lip service to'), which precludes people under 18 using the service. In addition, a spokesperson has said that people are aware of the risks, but choose to use the treatments anyway.

Now, however, an article on Stuff has shown that this isn't the case at all. The investigation carried out as part of the article showed that most of the sunbed operators looked into showed no signs of abiding by the voluntary code: they allowed underage clients to use them, and in many cases did not tell people about the associated health risks or even warn them to use the goggles provided.

Not OK, guys, not OK at all. After all, having your clients die is generally accepted, even in our gung-ho world, as bad (or at least unsustainable) business practice.

Thursday, 13 August 2009

Biomimicry and AskNature

It's a fascinating subject, and one of those which, like many great brainwaves, has that 'well, duh' component to it. Study nature's designs to see how its been doing things before trying to reinvent the [insert item here]. Well, of course!

Still, apparently it's something that has not been part of design dogma for some time. Silly us.

The gecko is definitely getting a fair amount of attention (see here and here, for starters) at the moment over its climbing ability, but nature abounds with brilliant things, and we're learning more and more from then, as this talk shows.

But now, there's this: AskNature, the site Benyus is working on. Because, of course, it's one thing to say 'well, study Nature before you design something', but it's an entirely different matter to attempt to first figure out what to study, and then how to access the data on it. Particularly if it's academic data and you are not, frankly, an academic. The site is another fine example of how freeing information up, not shutting it away, benefits everybody.

PopSci's Future Of...

Failing actual broadcast, streaming it would also be acceptable.

What is it, you ask? Why, this! PopSci's Future Of... And it's even getting good write-ups.

Of course, Popular Science is, itself, pretty cool, so we should have high hope for the programme anyway...

Intermission: engineering photo contest

Of course, as our imaging techniques grow in ability, so do the number and quality of photo competitions devoted to using them. (I remember submitting a couple of photos when I was doing my Honours degree).

They include

click on logo for link

Then there's Nikon's Small World competition (and brilliant website), dedicated to everything one can see with the use of a microscope.

Monday, 10 August 2009

Emissions target 2020

It's also somewhat below what Greenpeace had been vying for with it's 'Sign On' campaign (although we won't even get into that particular debate between Greenpeace and government...).

The reduction target is going to be tabled at tonight's talks in Bonn, Germany - for those not clamped in fascination to the workings of the UNFCCC, these are one of a number of meetings being held in the run-up to Copenhagen at the end of this year. Copenhagen should be very interesting, although I've heard mutterings saying that we shouldn't be too hopeful about the talks...after all, climate change and emissions reduction is a thorny issue for, well, everyone.

And it's a very tricky issue, not only internationally, but intranationally (my fancy way of saying 'here'). New Zealand certainly has a clean, green image, but this hasn't been borne out by fact recently, so there's a great deal of work to be done. Costly work. We're also an agricultural nation, and methane is not exactly the least important of the greenhouse gases.

So there's a great deal of push and pull between economic and environmental concerns. Then again, one could always argue that, as with most things, there is a middle way. With appropriate R&D funding, means of being green could become sources of income. Forestry. Windmills. GM cows and their gut bacteria...

For some (far more) expert commentry on today's announcement, mooch on over to here.